In 2017 I analysed local authorities’ (LA’s) investments in the area of sports in Poland. While going through their budgets I got more and more curious about the place of professional sports clubs in this field. In nearly every large city the investments and grants provided for ‘sport for all’ projects were considerably smaller than the amount of grants or activities aimed at professional sports clubs.

Indeed, the public financing of professional sports clubs in Poland quite notorious. While most of the clubs are private organizations, most are by some means organizationally and financially assisted by the relevant local authority. Furthermore, in a number of cases, local authorities actually play the role of a club’s saviour, supporting them by commissioning public-facing projects such as promoting the city as a tourist destination. One might think this would be questionable route for LAs to go down, given that the (football) clubs are a potent ground for right-wing radicalism are hard to separate them from fan-related hooliganism.

Nonetheless, the figures and my research lead me to another question: If in fact professional sports clubs in Poland are often publicly supported or are publicly-owned entities, how socially responsible are they?

How to analyse sports clubs’ social responsibility?

Together with a group of Polish researchers interested in CSR in sports we decided to gather data that would enable us to answer this question. First, we developed a tool based on good practices of responsibility in sports, and consulted on it with multiple stakeholders interested in the topic. As a result, we built a survey consisting of about 110 binary questions related to the topic of social responsibility, social and environmental impact, good governance, and sustainability. In the actual final study we analysed a range of topics considered good practices in the area of social responsibility in sport, recognising that, at that point, we were not able to go deeper into the responsibility of practices e. g. towards employees or partners and thus the results might seem to cover only a façade of CSR.

Nonetheless, in comparison to some other tools describing good governance, our index was not focused entirely on procedures, but involved analysing sport clubs’ activities. For example, while asking about transparency we inquired whether clubs published the reasons behind their critical decisions, such as releasing a coach. In a similar vein, while analysing activities to counter xenophobia, racism, and violence, we took into considerations whether in cases of such incidents, they were officially and publicly criticized by management on a club’s website.

The pivotal success of this project was that all five of the largest leagues (football, speedway, basketball, volleyball, and women’s volleyball) in Poland supported our analysis, helping us to reach relevant people in the clubs’ structures and make first contact much smoother. This way the study became a two-sided interaction, and we were able to conduct interviews with representative of nearly half of the 78 teams included in the study.

However, even though the actual levels of CSR, as analysed with the tool, were very low (just three clubs exceeded an average score of 30%), the study and report has not caused much outrage or shock among the subjects. On the other hand, multiple media outlets showed interest in the content, and several media stories were published based on our results.

Starting the second edition of the survey

With the positive feedback and interest outside academia at the beginning of the 2019/2020 football season, we have decided to repeat the exercise. However, based on the first edition the decision has been made to limit the sample to clubs playing in PKO Ekstraklasa – the top football league in Poland. The reason is pragmatic – football clubs are the largest and most impactful sports organisations in the country, and the size of an organization strongly correlates with the ‘range’ of responsibility as analysed in this study. Another reason is that our primary technique to gather data continues to be content analysis (website, published documents and social media) and we found that smaller organisations usually do not share much information on their media platforms, which tended instead to focus on the very core of their activities, i.e. first team competition.

Clubs playing in the PKO Ekstraklasa are facing turbulent times – in terms of sporting success the whole league is in an enduring crisis which manifests itself with lack of international relevance (Poland is classified below Belarus and Azerbaijan in the UEFA coefficient), with clubs struggling to make it out of the qualifying rounds of both the Champions League and Europa League. This is one of the reasons why public investments in sports clubs in Poland have become more scrutinized than ever, i.e. is such financial assistance ‘worth it’? Furthermore, sports media spend most time witch-hunting those responsible for the lack of sporting success, seeming more like solution-seekers rather than focusing on the competition itself.

Nonetheless, recently, the popularity of football in Poland has led to multiple public investments in Ekstraklasa, including: a record-high TV deal with the state television company, Prime Ministerially led programmes to help clubs with infrastructural investments, the Ministry of Sport and Tourism undertaking programmes to identify talented youngsters, and public companies (PKO BP, Totalizator) becoming or extending their high value sponsorship deals with Ekstraklasa. One might say that the international weakness of PKO Ekstraklasa has become a national issue and all (public) hands are on deck.

All those reasons aside – Polish football, as in many other countries – has some unique challenges ahead. For example, with its popularity it mirrors many conflicts present in modern Polish society, making sports clubs and football stadiums places of political debate on topics such as religion, migration or history (which sometimes get out of control).

Therefore, the focus on PKO Ekstraklasa does not imply a limitation of our study – in fact the analysis might become even more appealing to the general public and stakeholders, precisely because of this focus. The aim is also to make the report more convenient and accessible to fans. In the first edition we focussed on distinguishing leaders and good practices, intentionally limiting opportunities for ‘blaming and shaming’. In the second edition we plan to write a short ‘report card’ for each of the football clubs. Hopefully, once again the analysis will become an introduction to a wide-reaching discussion about the responsibility of sports clubs in Poland.

About the project

The main aim of project is to analyse the social responsibility of professional sports clubs in Poland. Its goal is to regularly assess and publish information regarding Polish sports clubs’ social responsibility as a way to educate clubs and their stakeholders. Other, secondary, goals are to disseminate knowledge about social responsibility in sport, to promote good practices in this area and, in the long run, to spur sports clubs in Poland towards a greater involvement in social responsibility.

The project itself is based on the Sports Clubs Social Responsibility Index (SCSRI) – a tool which we developed to analyse the social responsibility of professional sports clubs in Poland. In order to develop the tool, in the first phase, we conducted analysis of specific understandings of social responsibility in reference to professional sports teams, and collected best practices as described by the organizations involved in social responsibility in sport e. g. FIFA, UEFA, Healthy Stadia, European Football for Development Network, European Club Association, Expert Group „Good Governance” (EU), Transparency International, UK Sports (A Code for Good Governance), the German Federal Ministry for the Environment (Green Champions in Sport and Environment), Fare network (formerly Football Against Racism in Europe), Cafe Football etc.

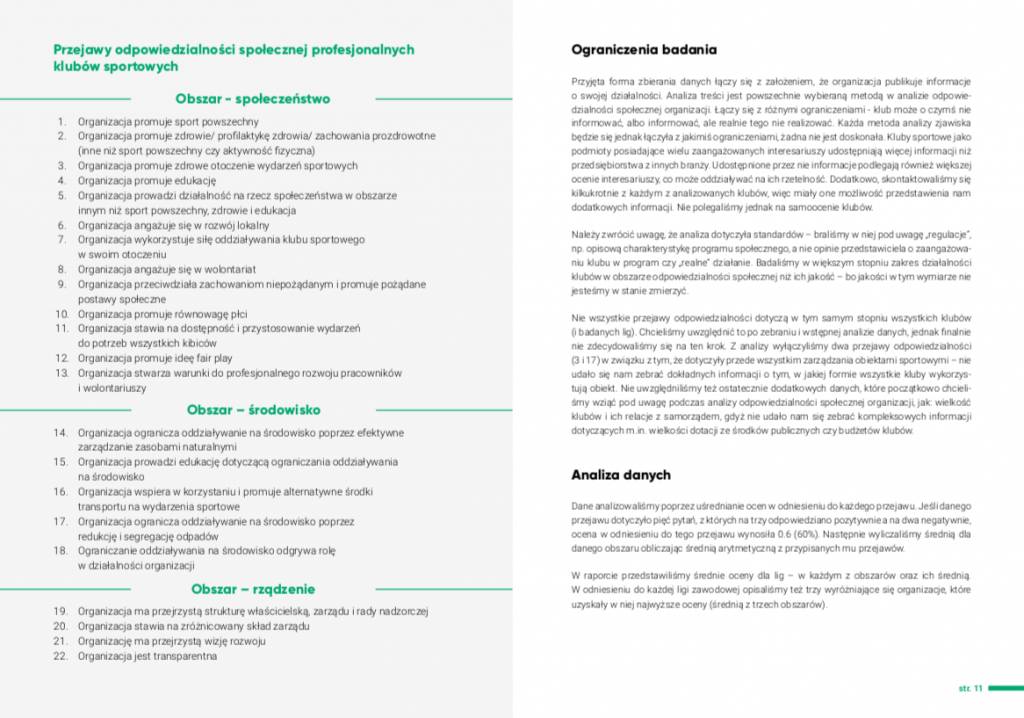

In the second phase we translated those practices into 22 general questions (each were translated into multiple binary questions) which fitted into three categories of responsibility: social, environment, governance. In the next step, we shared and consulted the preliminary tool with different sport clubs’ stakeholders to get their take on the procedure and questions.

In addition to content analysis, in the first edition of the study we conducted over 30 interviews with the sports clubs’ representatives in Poland, which further enhanced our understanding of social responsibility in this specialised context. As a result, in the second edition several changes regarding the tool have been made, such as procedures regarding clubs’ policies regarding employment practices, child protection, safeguarding, and wellbeing. With the understanding that the tool is always evolving, it should still become a specific and up-to-date reference point for the clubs.

The first edition of the project was coordinated by the Social Challenges Unit at the University of Warsaw. Researchers from five universities and research institutes were involved in study: University of Warsaw, University of Lodz, University of Physical Education in Warsaw, University of Physical Education in Wroclaw and Polish Institute of Sport. Five teams of over 25 students were involved in data collection.

The final report (I edition, in Polish) can be downloaded here.